Connect-4 AI

A while back I created an AI that played connect-4 at a level that no human it played against could top. The project is on my github if you want to check it out. Forgive me, as the project isn’t the cleanest code I’ve ever written, inconsistent casing, and run-on files.

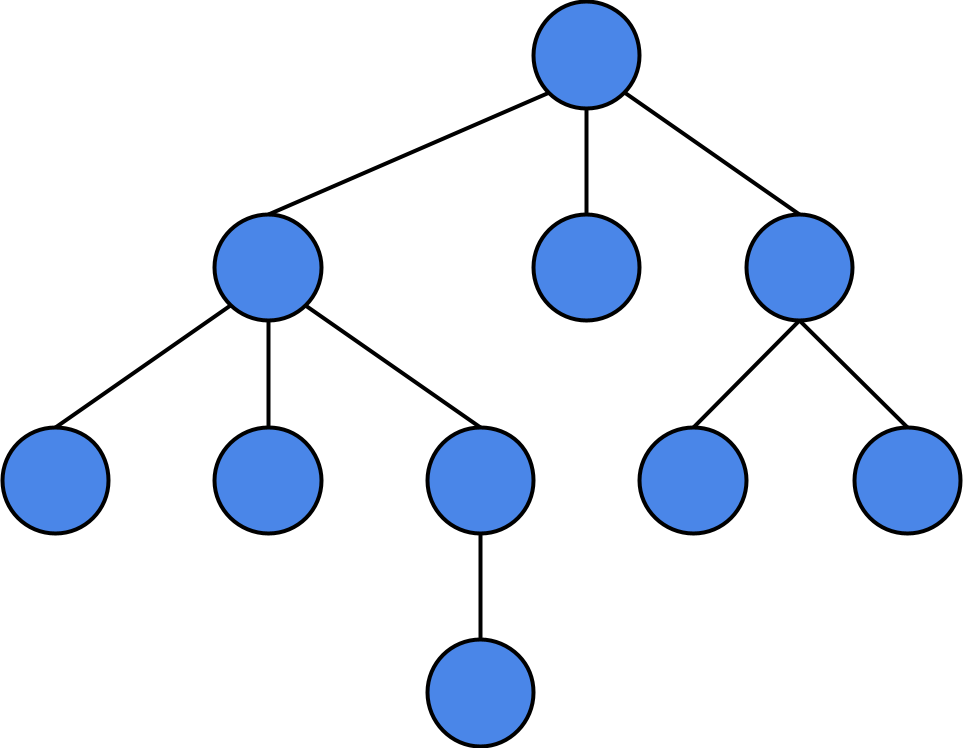

It works using an algorithm known as “Minimax”. Minimax is a relatively simple algorithm. You can imagine a game in the form of a data structure called a “tree”. A tree has nodes(aka. leaves), and each of these nodes has connections(aka. branches) leading to other nodes. These connections are 1-directional, from “parent node” to “child node”.

We can represent a state of the game as a node, and any action made by one of the players can be represented as using a connection to move to another game state lower on the tree.

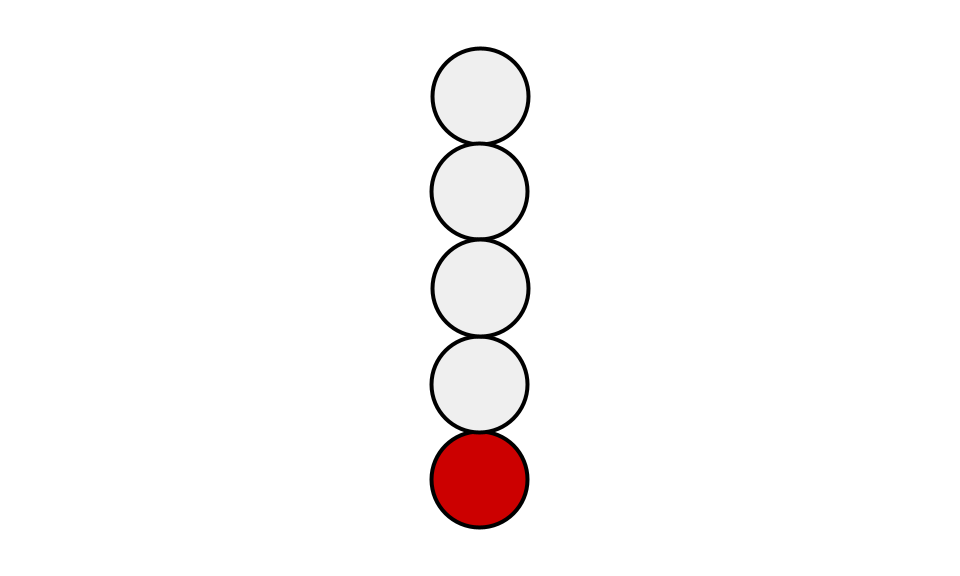

Now that we have this model of a game, what can we do with it? We can start with a simpler game, nim. Nim is a 2-player game where there is a number of tokens stacked vertically on a table, all the tokens are white, except for a red token at the very bottom of the stack. 2 players take turns drawing 1,2, or 3 tokens from the top of the stack. Whoever draws the red token wins.

Different variations of the game have a different number of tokens to start, and different numbers you’re allowed to draw, and they don’t usually give the bottom token a different color(although removing the final token it is still the objective). Some versions of the game have several stacks, and whoever empties the last stack standing wins. But the principle is the same.

Our example game will have 1 stack of 5 tokens, you may draw 1, 2, or 3 tokens from the pile, and two players, Alice and Bob are playing against each other, and Alice goes first.

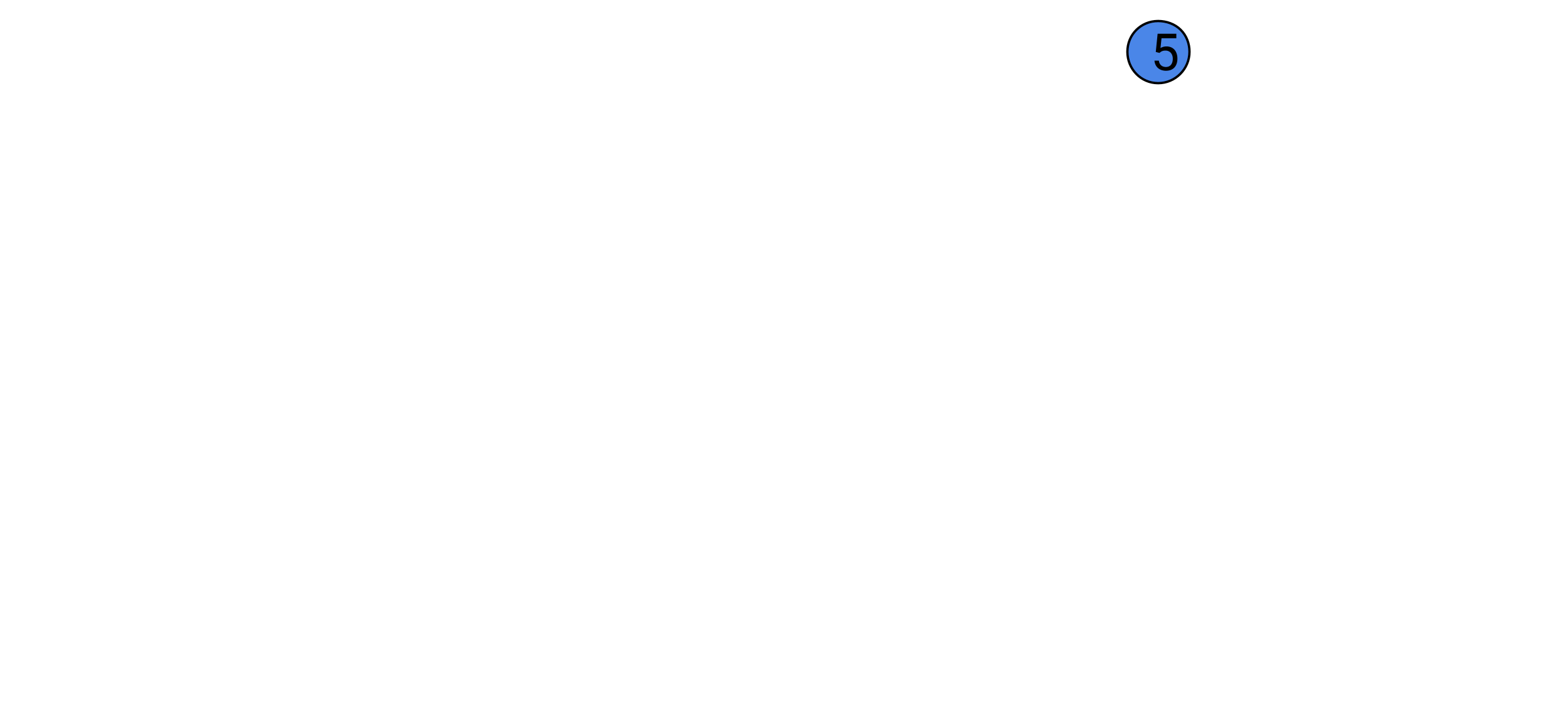

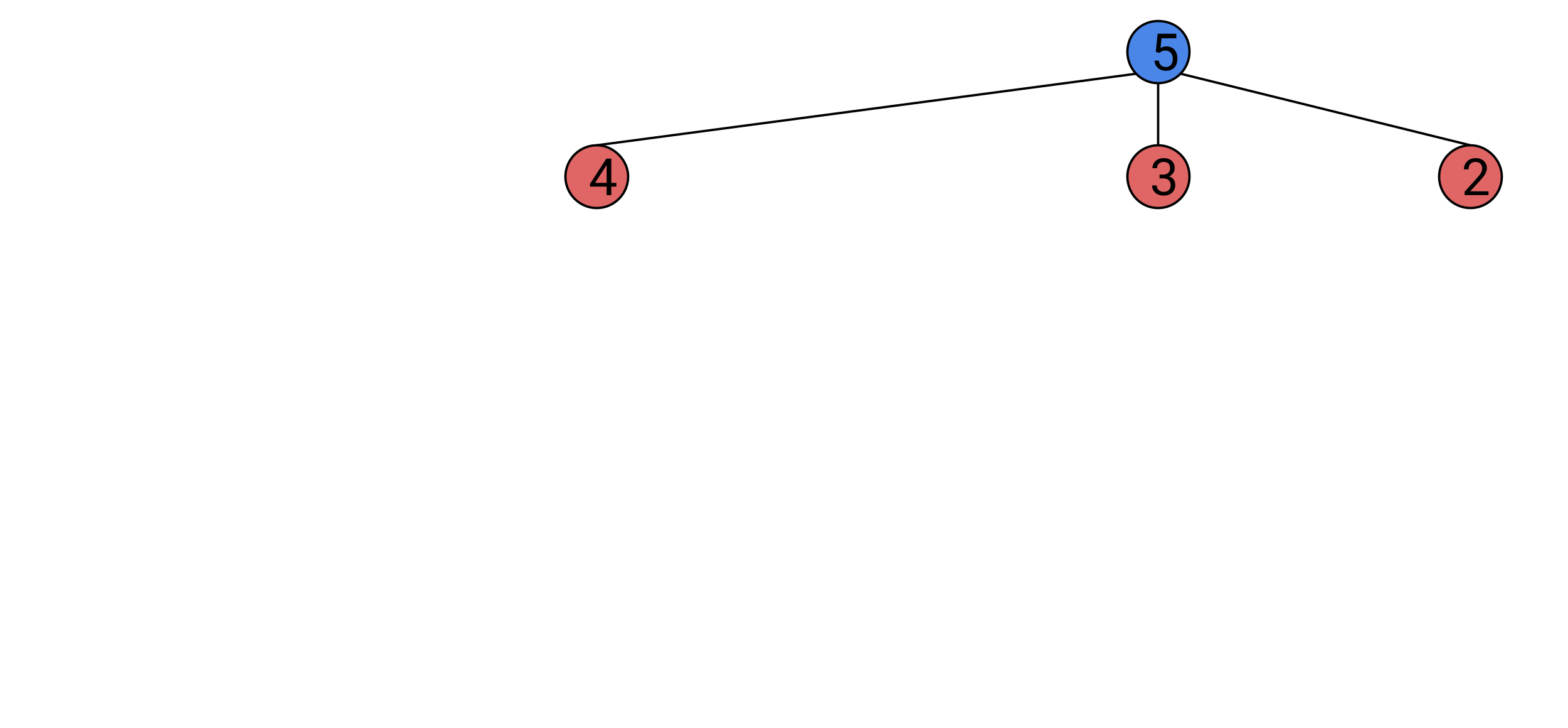

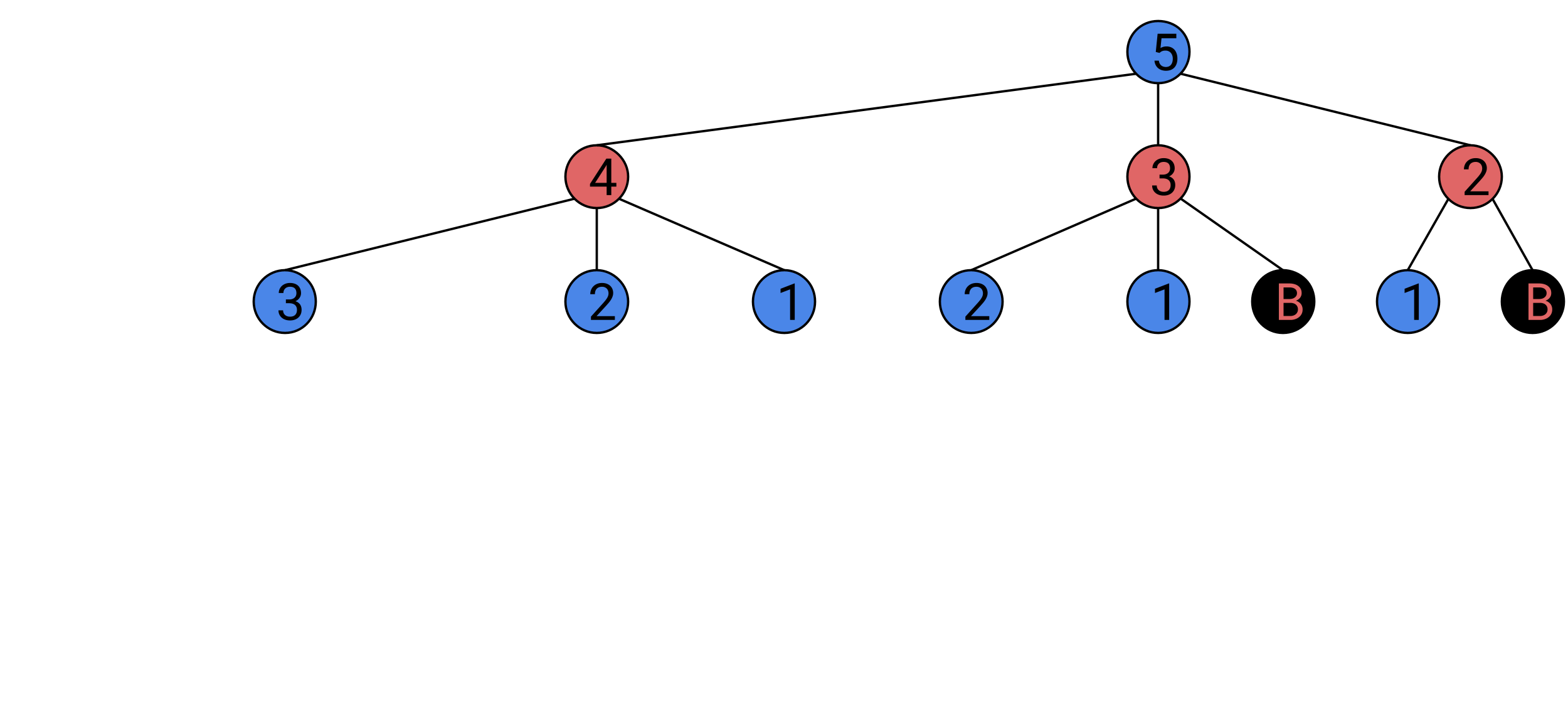

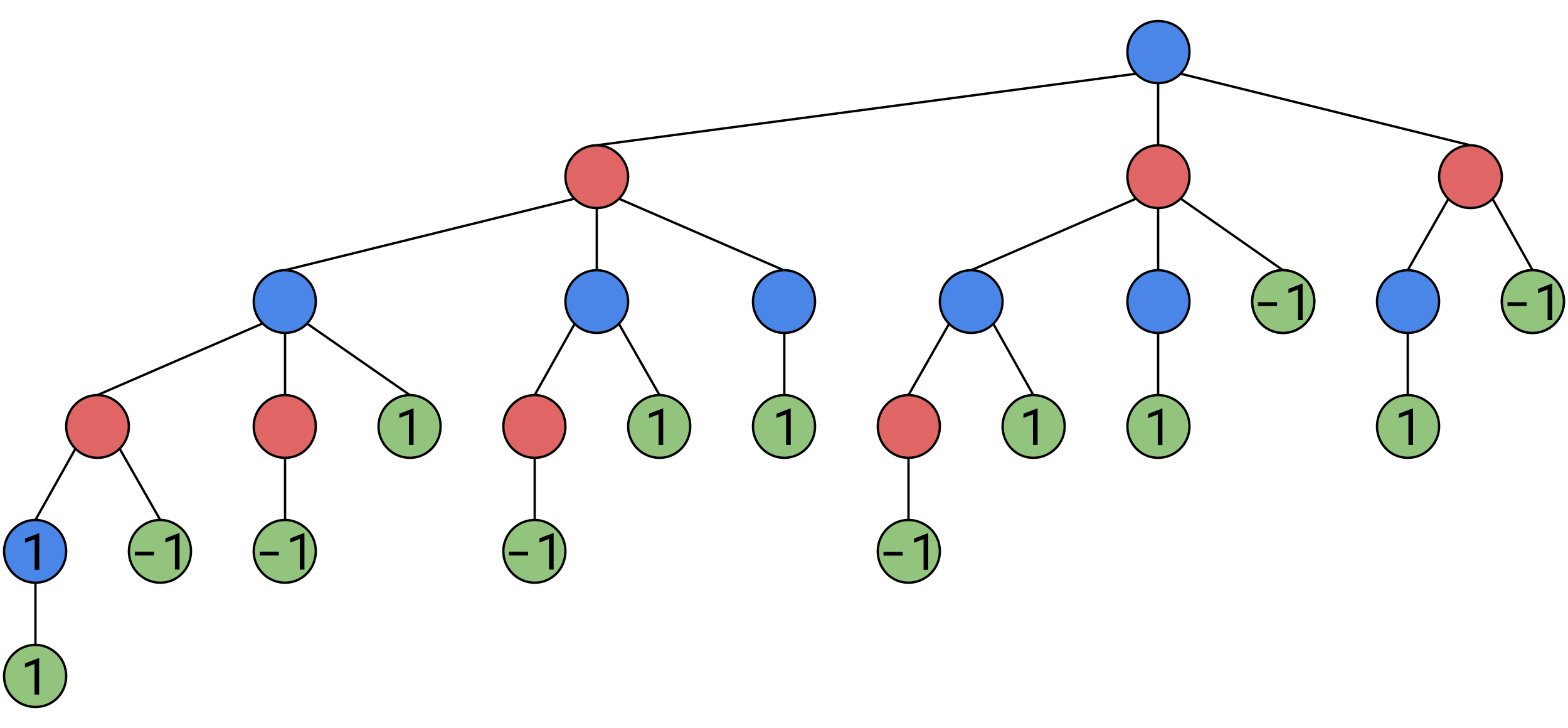

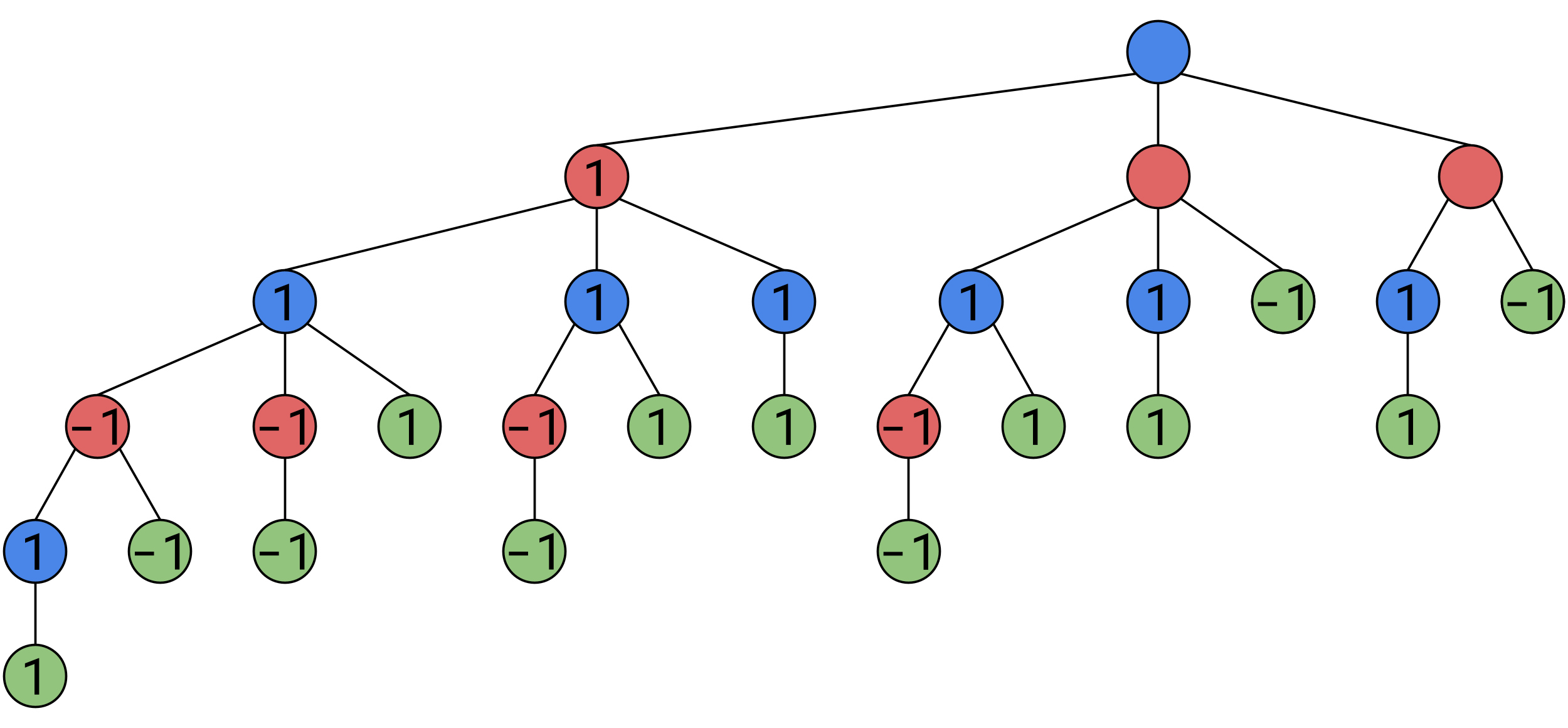

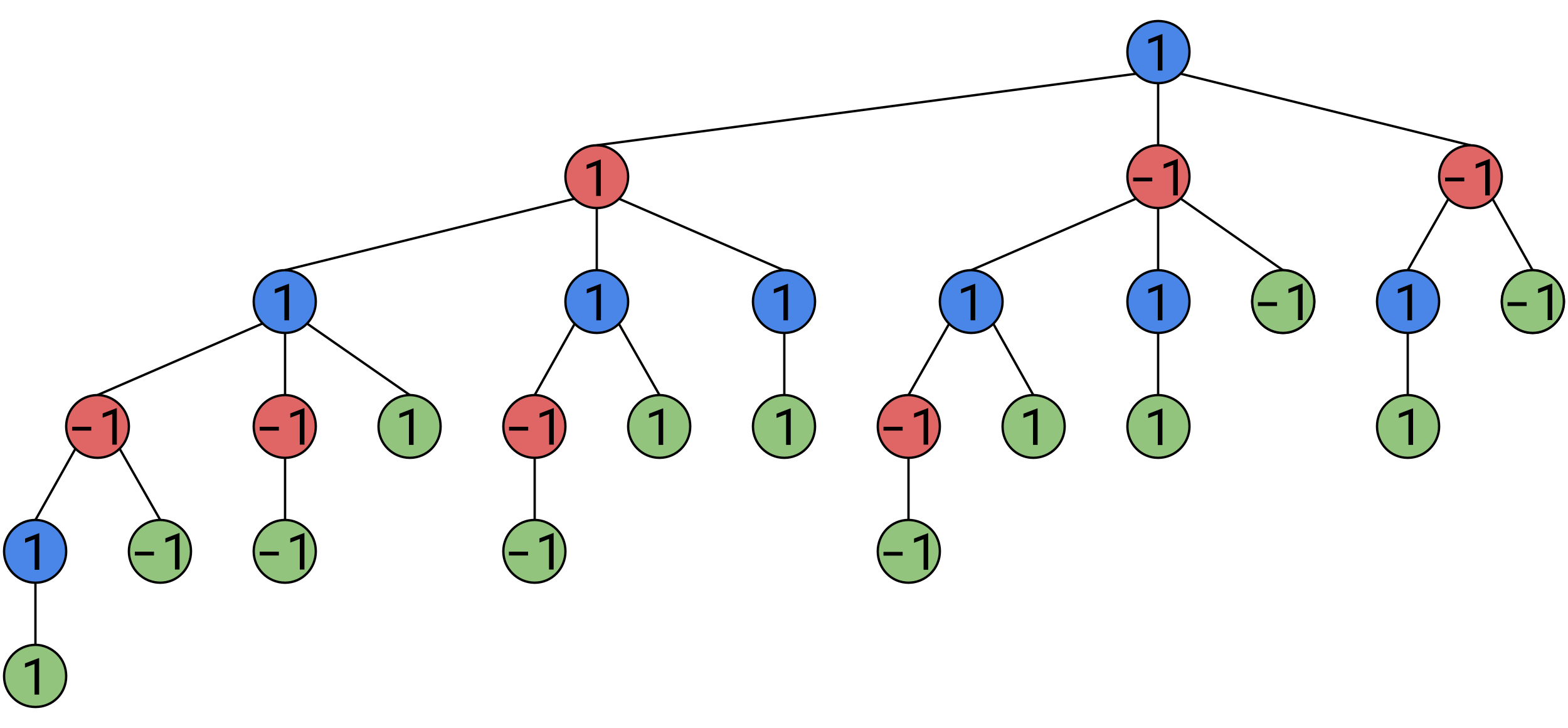

We start by drawing the node of the starting state of the game. Blue nodes are Alice’s turn, reds are Bob’s. The number in the node represents the total number of tokens left on the table.

We then draw the three other states Alice can change the game to, and the connections to them.

We now draw the three states Bob can create from each of these states,

You may notice that in one of these new states, Bob has won the game, we will stop adding on to that branch, but continue in this fashion for all the others, until all branches end with someone winning.

Once we have this tree, we can now use the Minimax algorithm to determine the best move in any given state. I encourage you to try and figure out the solution for yourself before scrolling to the next paragraph.

Minimax starts by defining one player’s win as a high number, and the other player’s win as a low number(traditionally 1 and -1). We will say that positions where Alice wins have a value of 1, and positions where Bob wins have a value of -1. Now we can concisely define the goals of the players Bob wants to MINImize Alic wants to MAXimize MINIMAX

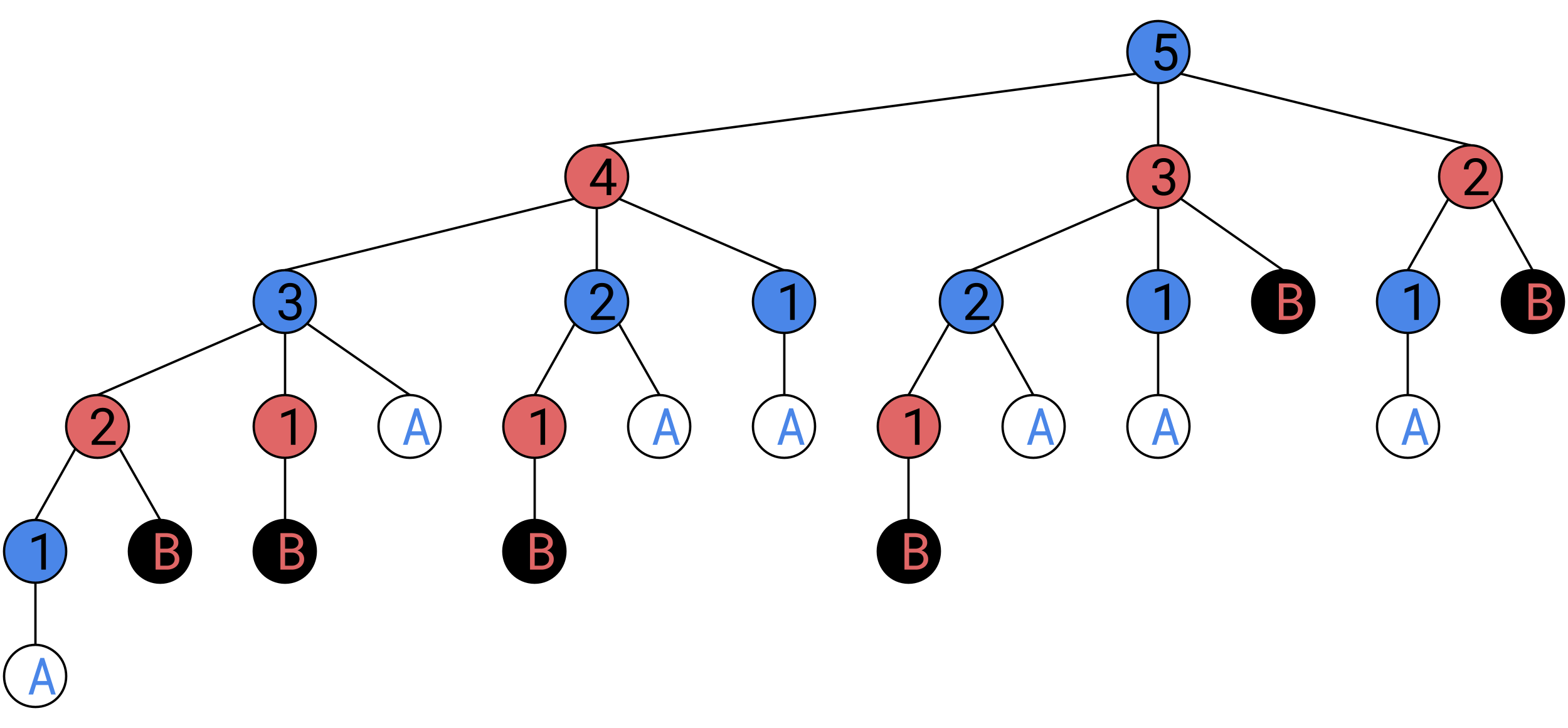

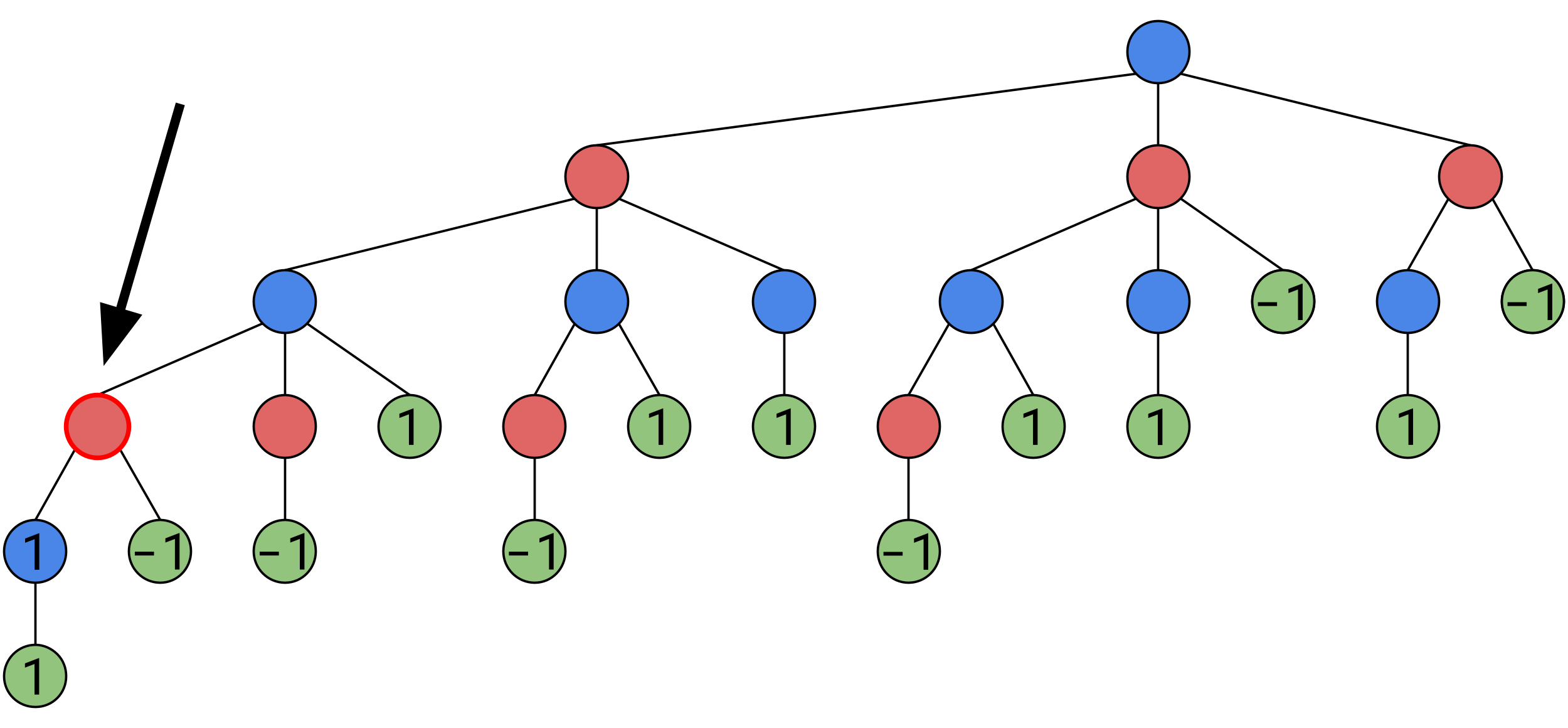

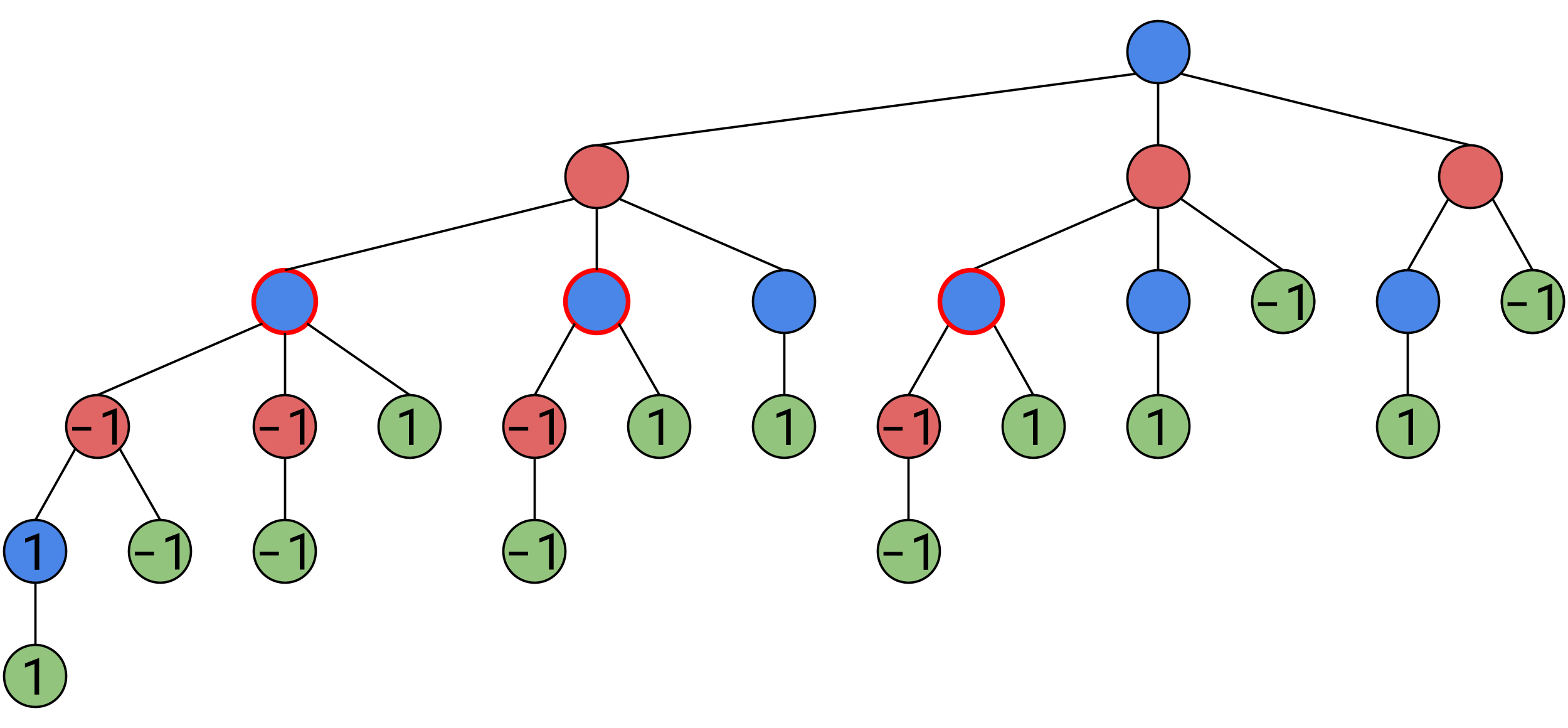

We’ll take away the numbers within the circles that represent how many tokens are on the board, and instead, the number now represents the value of the position, we’ll start by labeling winning positions 1 and -1 respectively.

Consider this node:

Here, Alice’s only option is to draw the final token and win, that position also has a value of 1, because once she has arrived in this position, her victory is inevitable.

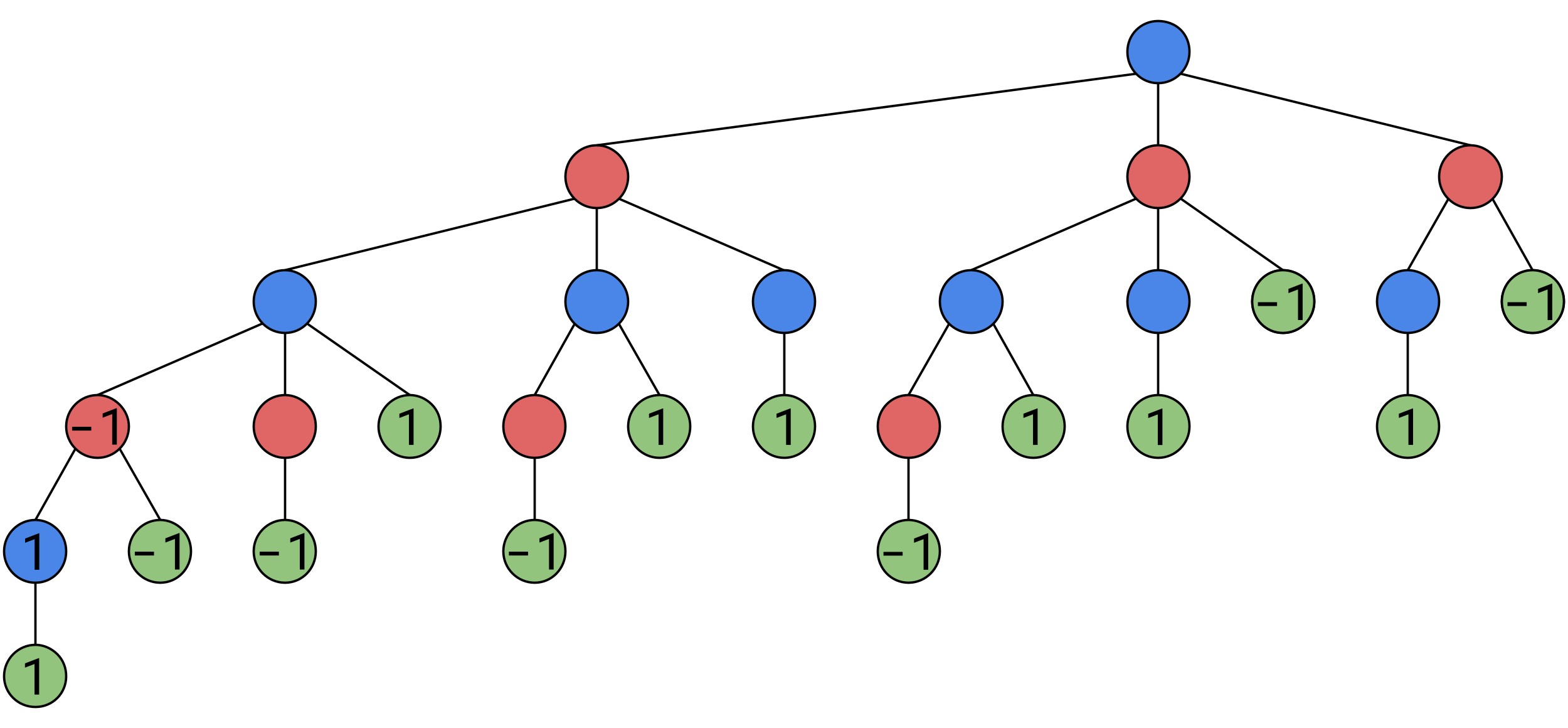

Now consider this node:

Here, Bob must pick between a position of value 1, and a position of value -1, now remember, Bob wins in a position of value -1, so he’ll pick that one. As this position places Bob in a position where ideal play will gurantee him a win, this position is considered a win for Bob, and itself has a value of -1:

And positions where Bob is guranteed a win regardless of how he plays, are also considered to have a value of -1:

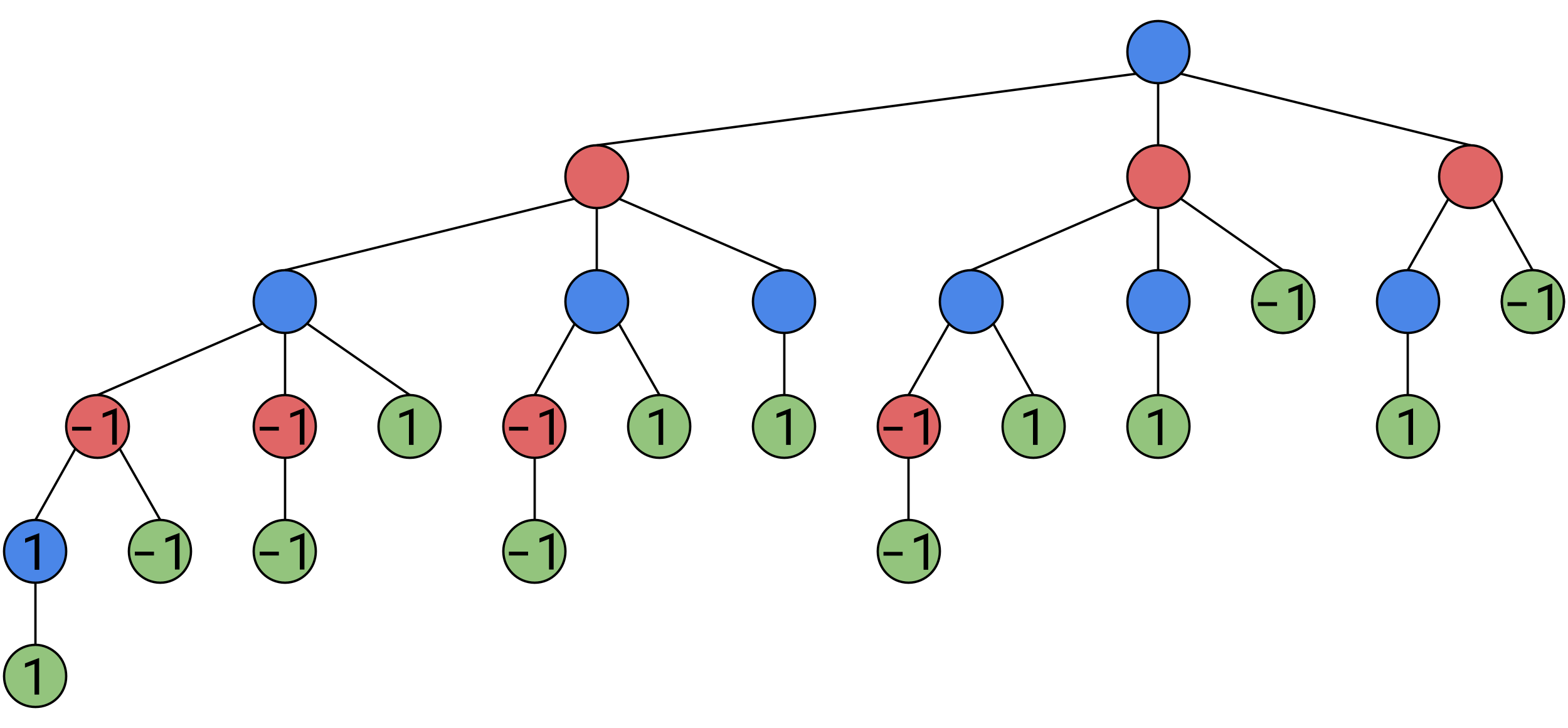

Now consider these nodes highlighted:

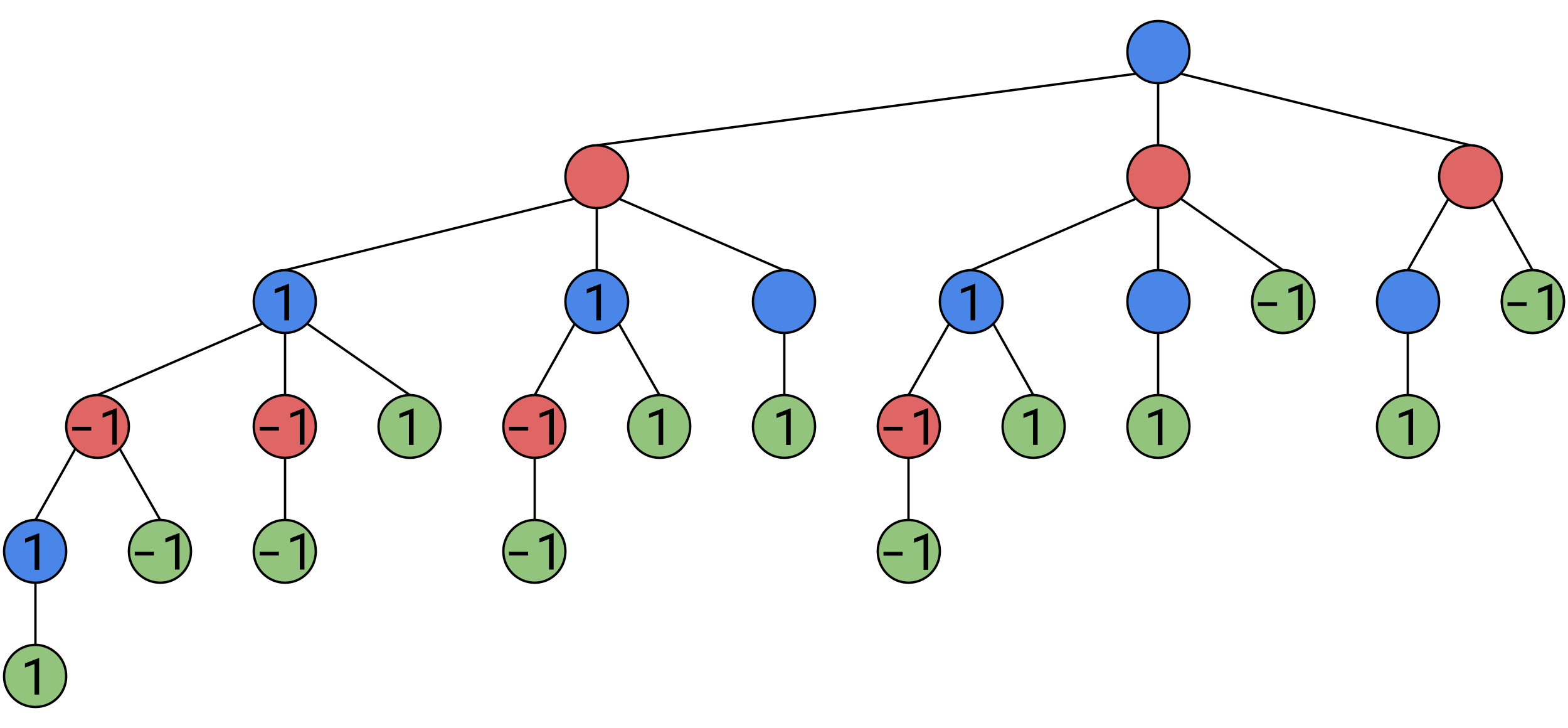

We can generalize our logic to something more concise, when it is Alice’s turn, she will maximize the value of the next game state, when it is Bob’s turn, he will minimize the value of the next game state. So each of these junctions have a value of 1.

We fill in other guranteed Alice-wins on this layer.

And consider this node:

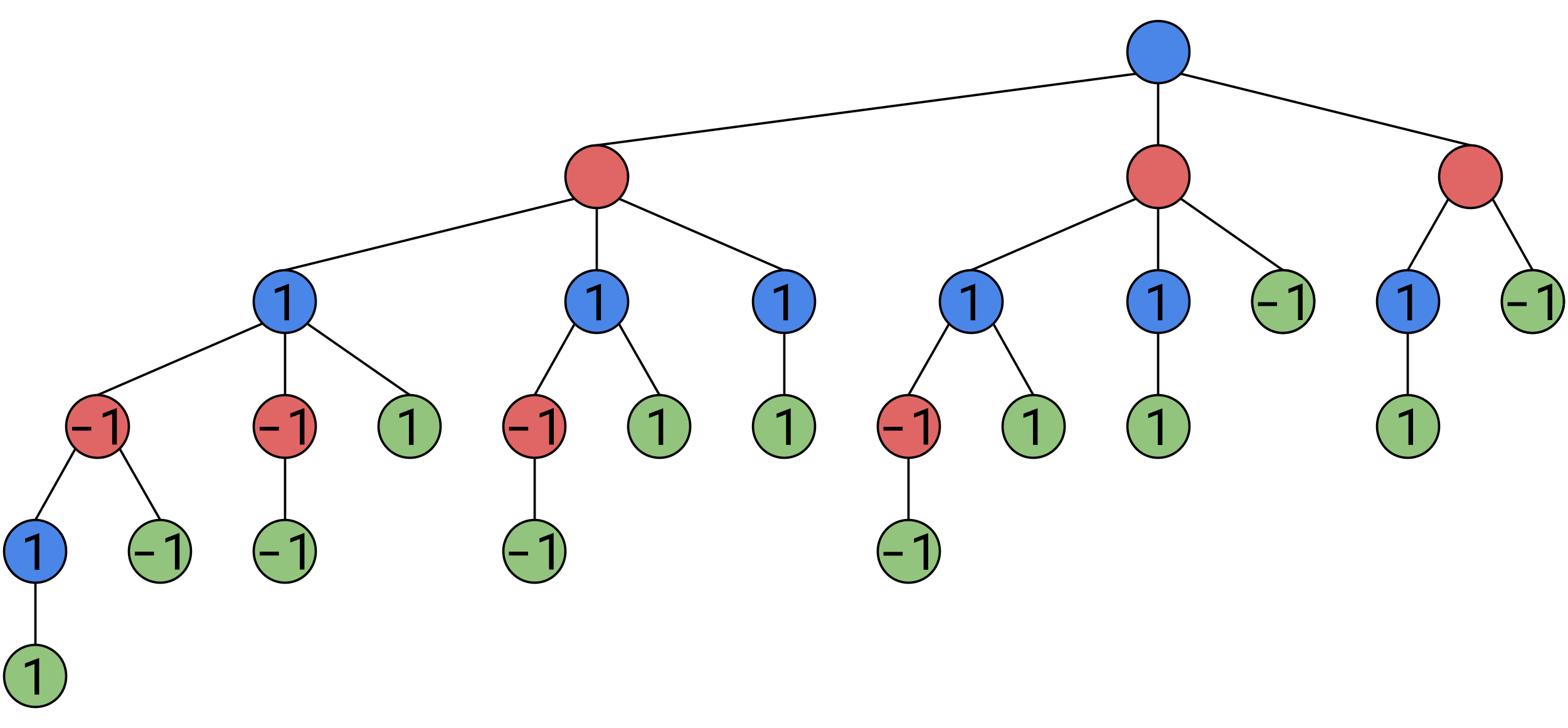

Here, no matter what Bob does, he will find himself in a position of value 1, no matter what he does, Alice will win on every path, therefore, even though it’s Bob’s turn, the position has a value of 1.

Continuing this process up to the top, we find that the game was rigged in Alice’s favor from the start, she can force a win:

In nim this process is relatively simple, and can be bruteforced, but for more complicated games such as chess, the tree is simply too big to bruteforce.

So what we do instead, is we go a set number of layers deep into the tree, and we apply a function to the gamestate to estimate the value of the position. Sometimes this function is coded manual(or hardcoded as we like to say), but for more complex games, this is rarely good enough. Instead, we feed the gamestate into a sufficiently advanced technology to estimate the value of the position.

Clarke’s Laws:

- When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

- The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.

- Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

The sufficiently advanced technology used to estimate the value of the position is called an “Artificial Neural Network” (aka. Neural Network, aka. Neural Net, aka. ANN)

It is very math heavy, and it runs on the GPU to be extra efficient. Nobody really understands exactly why the solution works, we just know how to use it, and that it works very well for many kinds of problem.

How did we come up with it? We studied brain cells, and created a grossly oversimplified digital representation of one that can get the job done just fine if there’s enough of them. They can learn to approximate nearly any function to impressive accuracy, sometimes with negligible error, including the behavior of real brain cells(which we still don’t fully understand).

Then we throw data of previously played games at it, tell it who won, and it will learn from this example to evaluate positions more accurately.

Where do we get this data of previously played games? We either take it from human games, or have the AI play against itself as it improves(which is what I did).

I’ll go into more detail on it in a later blog, as it’s a deep technical and philosophical discussion in it’s own right.

(Game tree with values on base cases)

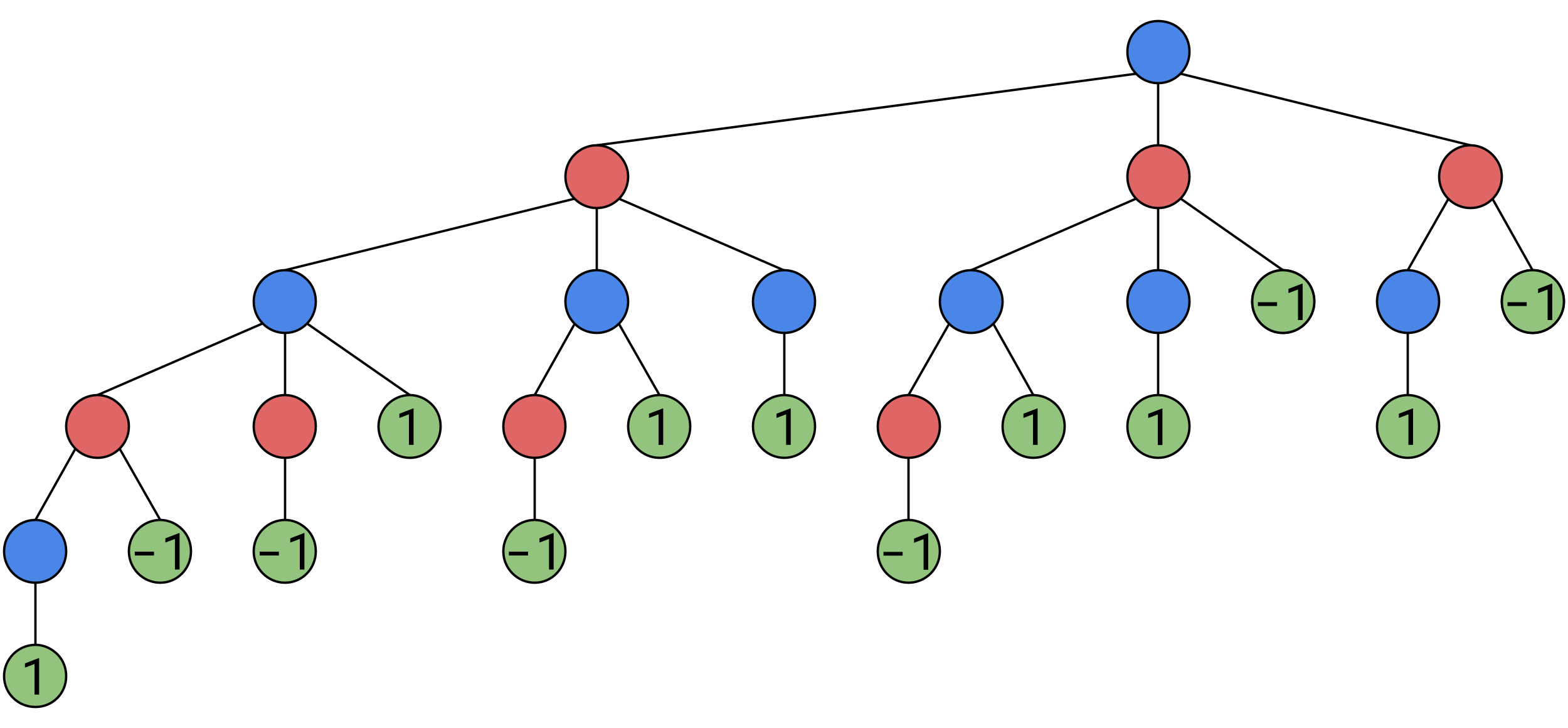

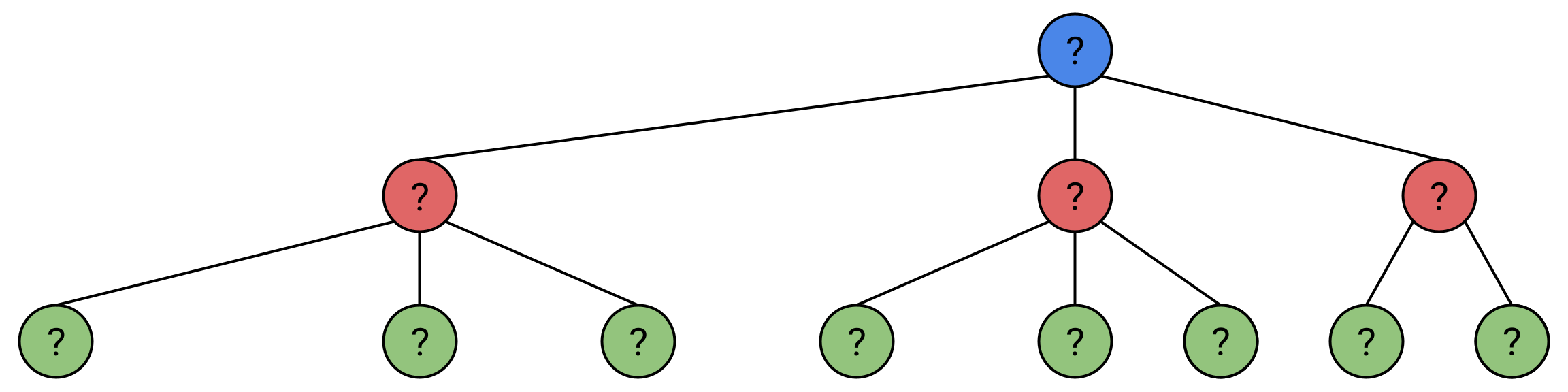

So we now have this tree, where we have our values estimated by an ANN once we reach a certain depth, and with those values propagated upwards appropriately. But there are some shortcuts we can take to get the same answer, faster.

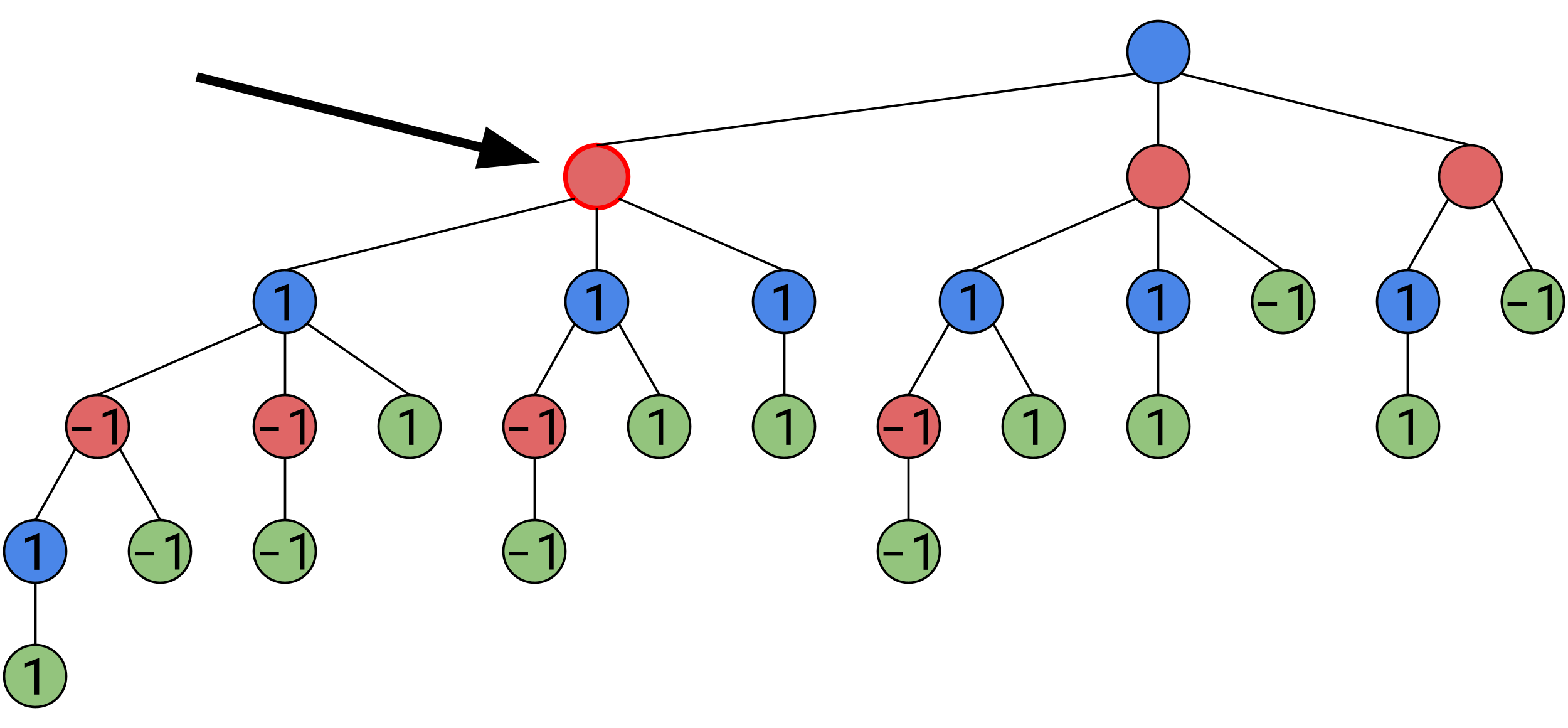

This particular optimization is called Alpha-Beta pruning, and can take a second to wrap your head around.

Alpha-Beta pruning is easier to show visually than explain verbally.

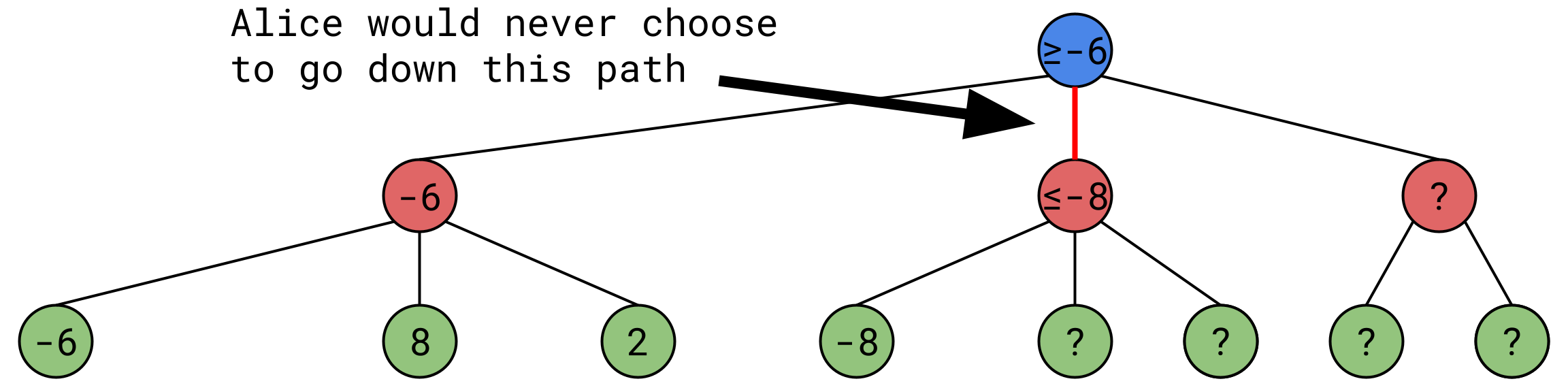

In this diagram, “?” is a state we haven’t yet fed through the neural network, and we don’t know it’s value yet, Alice(white) is maximizing(she wants a state of as high a value as possible), Bob(black) is minimizing(he wants a state of as low a value as possible). The circled state represents where we are in our search.

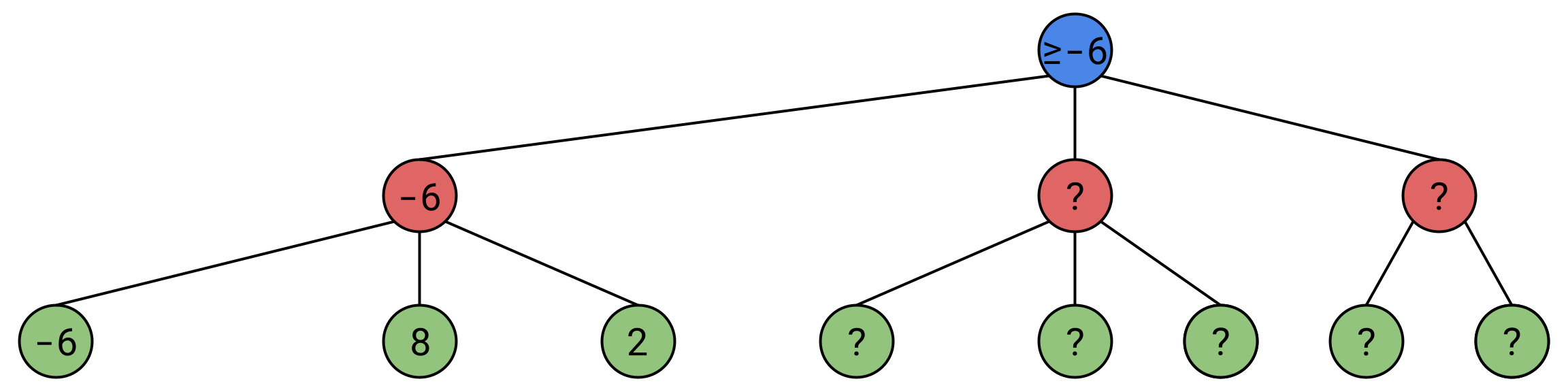

Say we explore a few nodes:

We know that at Alice’s node, no matter what we explore next, this node’s value will not go lower than -6. This is because if a route of value -7 or lower were discovered, Alice simply wouldn’t take it. Therefore, this node’s value is equal to -6 in the worst case scenario, but if we discover a better path, it may be greater than -6, so this node’s value, is greater than or equal to -6.

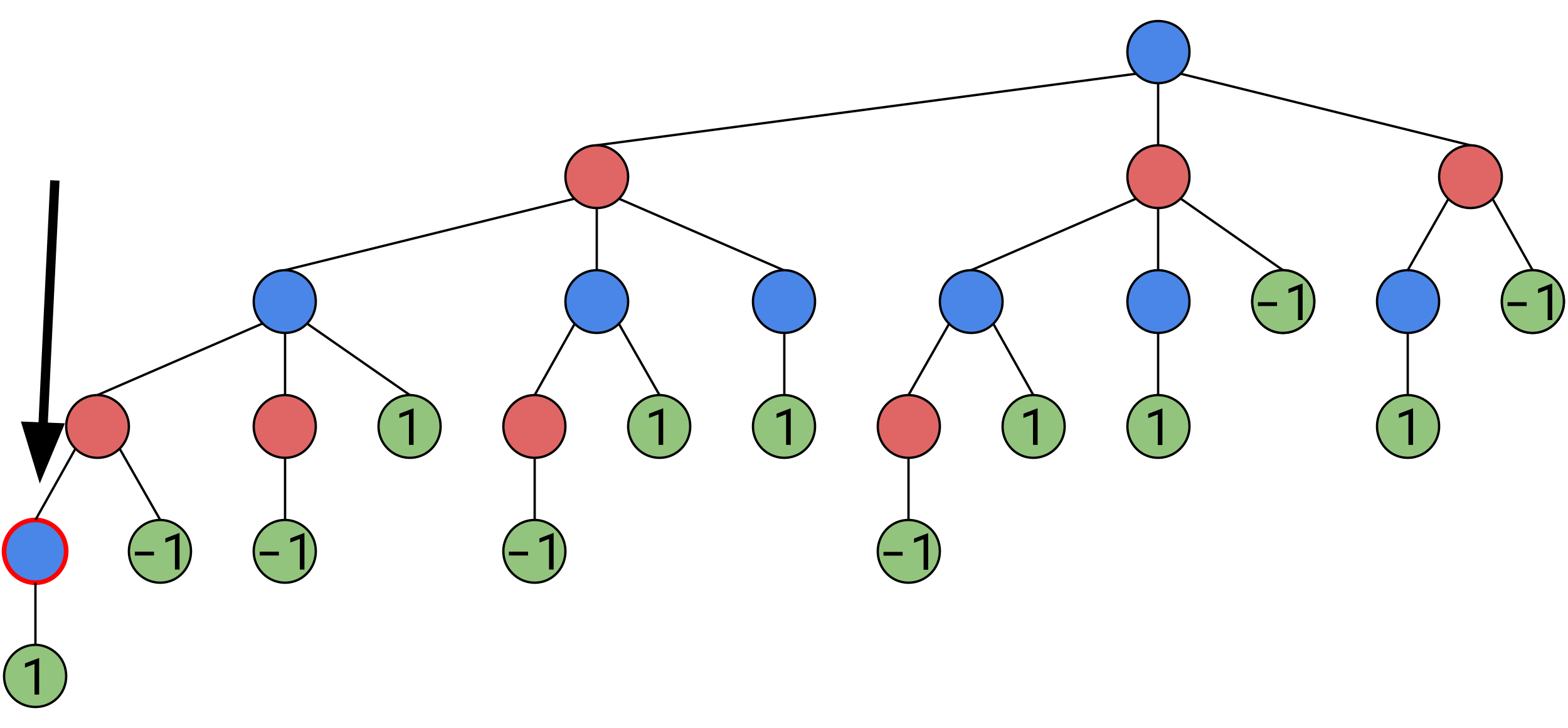

Now say we explore a little more:

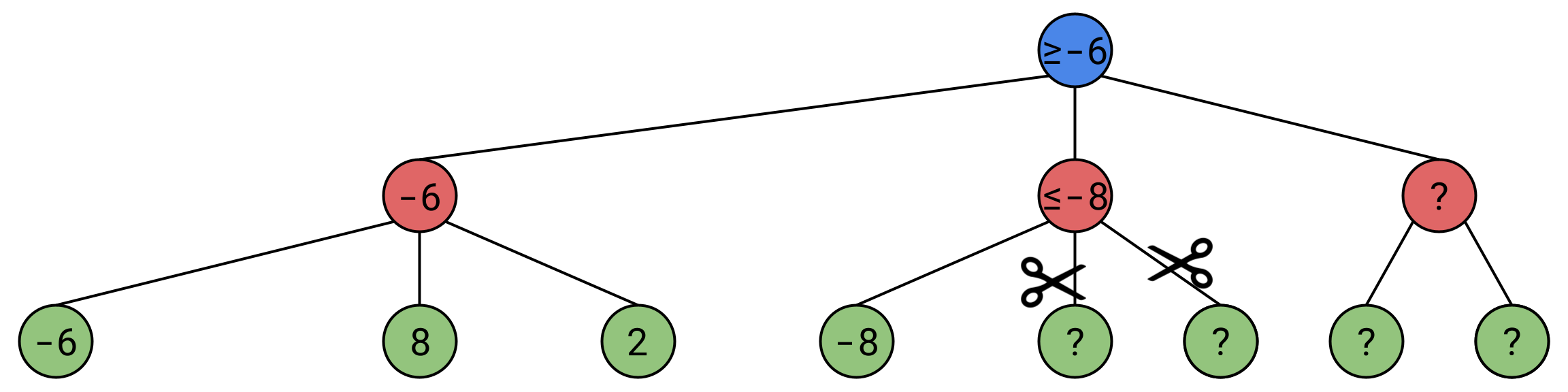

Now Bob finds himself in a similar situation, he has found a position very good for him, with a value of -8, if he finds a position whose value is greater than -8, he simply won’t take it. Therefore, this position’s value will always be less than or equal to -8.

But would Alice ever go down such a path? No! We already know that no matter what we find down this path, there will always be a better option for Alice, so there’s no point wasting computing power on exploring Bob’s remaining options. So we can disregard these extra 2 nodes, or “prune” them, to stick with the tree metaphor.

This is a far more efficient way of traversing the tree, and if you can traverse the tree more efficiently, you can afford to go a little deeper, which yields more high-quality moves from the AI.

You can find a link to the project on my Github